For millennia, cats have maintained an air of mystery that both fascinates and frustrates their human companions. Among their many enigmatic behaviors, one of the most puzzling is their tendency to remain silent when injured or in pain. Unlike dogs, which often whimper or vocalize discomfort, cats frequently endure suffering in stoic silence. This behavioral difference stems from a complex interplay of evolutionary biology, neurophysiology, and species-specific survival strategies that have shaped feline pain responses over thousands of years.

The evolutionary roots of feline stoicism run deep into their ancestral past. As solitary hunters rather than pack animals, wild cats couldn't afford to show weakness that might attract predators or competitive rivals. Vocalizing pain would have made vulnerable individuals targets in the harsh landscapes where their ancestors evolved. This biological imperative became hardwired into domestic cats, despite their comparatively cushy modern lifestyles. Even well-fed housecats retain these ancient survival instincts, often hiding illness until it becomes severe enough to overcome their natural inhibitions.

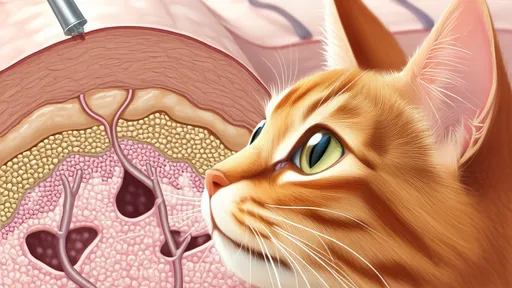

Modern veterinary science reveals that cats don't actually feel less pain than other mammals - their pain perception thresholds are remarkably similar to humans in many cases. The difference lies in how they process and express that sensory information. Feline pain pathways involve sophisticated neural filtering mechanisms that suppress outward displays of discomfort. Researchers have identified specialized inhibitory neurons in cats' spinal cords that modulate pain signals before they reach the brain, effectively creating a biological "mute button" for suffering.

This neurological filtering system serves several adaptive purposes. By minimizing pain responses, cats can continue essential activities like hunting even when injured. The ability to compartmentalize discomfort allowed wild ancestors to travel considerable distances for food and water despite injuries that might incapacitate more demonstrative animals. Contemporary domestic cats retain this capacity, which explains why a cat with a broken limb might still jump onto counters or a feline with severe dental disease may continue eating normally.

The social dynamics of pain expression in cats differs fundamentally from more gregarious species. In pack animals like dogs or humans, vocalizing pain serves important social functions - it summons help from group members and communicates vulnerability. But as primarily solitary creatures throughout their evolutionary history, cats developed no such signaling mechanisms. Their communication systems evolved primarily for territorial marking and mating rather than soliciting care, making them less likely to "speak up" about injuries even to trusted human companions.

Compounding this evolutionary legacy is the fact that facial expressiveness in cats developed mainly for intra-species communication rather than cross-species understanding. Where dogs evolved remarkably mobile facial features that humans can easily read, cats' subtle pain indicators - slight ear positioning changes, whisker adjustments, or minor pupil dilation - often escape human notice. Veterinary professionals train extensively to recognize these nearly imperceptible signs, but most pet owners miss them until the cat's condition becomes severe.

Recent advances in feline pain research have uncovered another surprising factor: cats may experience a form of dissociation between injury and discomfort that differs from mammalian norms. Imaging studies show that while their nociceptors (pain receptors) fire normally when injured, the emotional processing of that information in brain regions like the amygdala appears dampened compared to other pets. This doesn't mean they feel less pain, but rather that their conscious awareness of it may be neurologically muted - a phenomenon researchers are still working to understand.

The implications of feline pain masking extend far beyond academic curiosity. This behavioral tendency leads to widespread under-treatment of pain in domestic cats, with studies suggesting only about 13% of cats in pain receive appropriate medication. Many suffer needlessly from chronic conditions like arthritis because their stoicism fools even attentive owners. Veterinary organizations now emphasize the importance of presumptive pain management - treating likely sources of discomfort even without obvious symptoms - as standard practice for aging felines.

Understanding why cats hide pain ultimately helps us become better stewards of their wellbeing. By recognizing that silence doesn't equal comfort, cat owners can learn to spot subtle indicators like decreased grooming, changes in litter box habits, or altered sleeping positions. Modern veterinary medicine has developed specialized pain assessment scales that account for feline stoicism, helping bridge the communication gap between species. As we continue decoding the mysteries of feline pain perception, we move closer to ensuring our enigmatic companions don't suffer in silence.

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025

By /Jun 12, 2025